This is the first in a series of posts on automating blue-green deployments to Elastic Beanstalk using CodePipeline and Lambda.

I concluded my previous post by observing that one of the actions involved in the deployment pipeline for this blog’s WordPress application has direct knowledge of the environment to which it is deploying the application, citing this as a possible design flaw. As a matter of fact, both of the current pipeline’s actions have this knowledge.

Firstly, the action that deploys the application has this knowledge. This appears to be unavoidable when using CodePipeline’s default Elastic Beanstalk (EB) deploy provider: The name of an existing environment seemingly must be supplied to the provider in order for the action’s configuration to be considered valid.

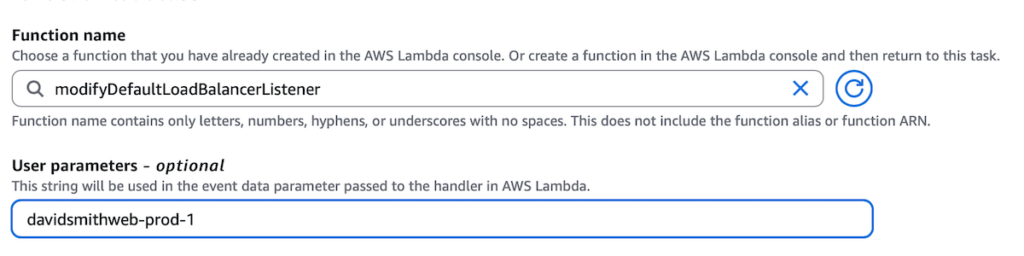

Secondly, the action that invokes the Lambda function that configures HTTP-to-HTTPS redirection for the application has this knowledge.

Notice that the name of the EB environment (davidsmithweb-prod-1), in this case supplied as user parameters, is static, meaning that this action can currently only work with a single, pre-existing environment.

I see this “need to know” as being problematic for a number of reasons. Firstly, it inconveniences the end user of the pipeline: Either they are forced to change the existing pipeline’s configuration to point to the new environment or they are forced to create a copy of the pipeline specifically for the new environment. Secondly, it increases the end user’s cognitive load in that they not only need to know how to do a deployment but also how deployments work. This is information they arguably shouldn’t need to know (another inconvenience). It may also increase the risk of errors during deployment, e.g., the end user easily could make a mistake when making the necessary pipeline-related changes, leading to the possibility of erroneous deployments.

Depending on the nature of the software project, design wrinkles such as these may need to be ironed out in order for the deployment job in question to be deemed acceptable for production use. Even on a personal project such as this they have proved headache-inducing enough for me to rethink the way the deployment job is designed. All of which brings me to the main topic for this series of posts—scripting deployments to EB such that the actions involved in the deployment no longer need direct knowledge of the environment. This scripted process will use a blue-green deployment strategy, so first a brief explanation of this.

Blue-green deployment

Blue-green deployment is a deployment strategy that calls for the existence of two production environments:

- A live environment that holds the current version of the application

- A staging environment that holds the next version of the application

Once the next version of the application has been tested in the staging environment, network traffic can be switched such that the staging environment becomes the live environment and the previous live environment becomes the new staging environment. (At this point the new staging environment can be terminated if needed, for example to save on hosting costs.) The terms “blue” and “green” are often used to differentiate between environments. Key benefits of this deployment strategy are zero downtime and easy rollbacks.

The following table gives an example of one possible blue-green deployment lifecycle. The example assumes that no environments already exist and that “blue” always corresponds to the live environment.

| Action | Environment 1 (app version) | Environment 2 (app version) |

|---|---|---|

| Create environment | Blue (current) | n/a |

| Create environment | Blue (current) | Green (next) |

| Swap environment domain | Green (previous) | Blue (current) |

| Terminate environment | n/a | Blue (current) |

| Create environment | Green (next) | Blue (current) |

| Swap environment domain | Blue (current) | Green (previous) |

| Terminate environment | Blue (current) | n/a |

The example depicts three deployment “cycles”: one initial cycle that operates on one environment and two subsequent cycles that operate on two environments. Notice the relationships between the environment name (1/2), the environment domain (blue/green) and the app version (current/next/previous). Also notice how the final “terminate-environment” action returns the system to the same configuration that existed immediately after the initial “create-environment” action—environment 1 is blue and holds the current version of the application. This demonstrates the cyclical nature of blue-green deployments.

The remainder of this series of posts will focus mainly on the specifics of implementing a workflow that supports this very lifecycle. Before we dive into these details, however, let’s first examine the high-level design of the deployment pipeline for this blog.

Deployment-pipeline design

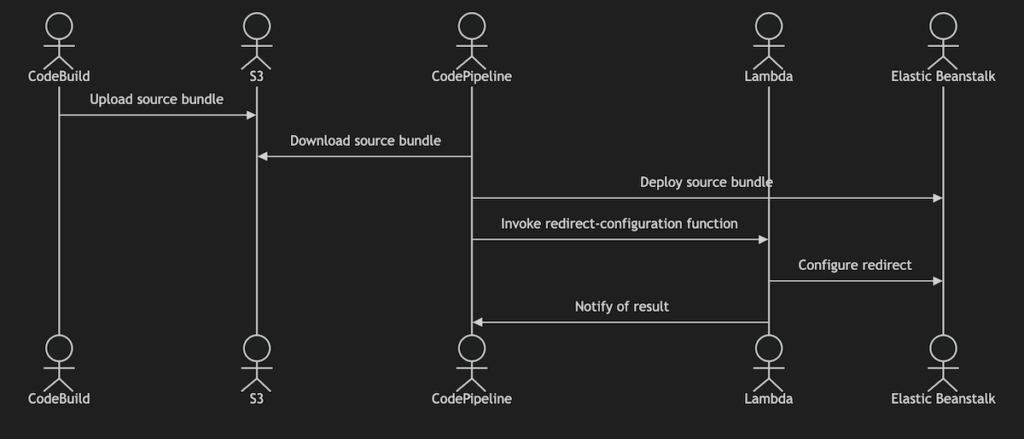

In its current state, the deployment pipeline for this blog involves the following actors and processes:

- CodeBuild pushes a source bundle to S3

- CodePipeline downloads the source bundle from S3 and deploys it to an existing EB environment using CodePipeline’s built-in deploy provider.

- CodePipeline invokes a Lambda function for configuring HTTP-to-HTTPS redirection

- The Lambda function attempts to apply HTTP-to-HTTPS redirection to the EB environment and notifies CodePipeline of the result

Or, to express this as a diagram:

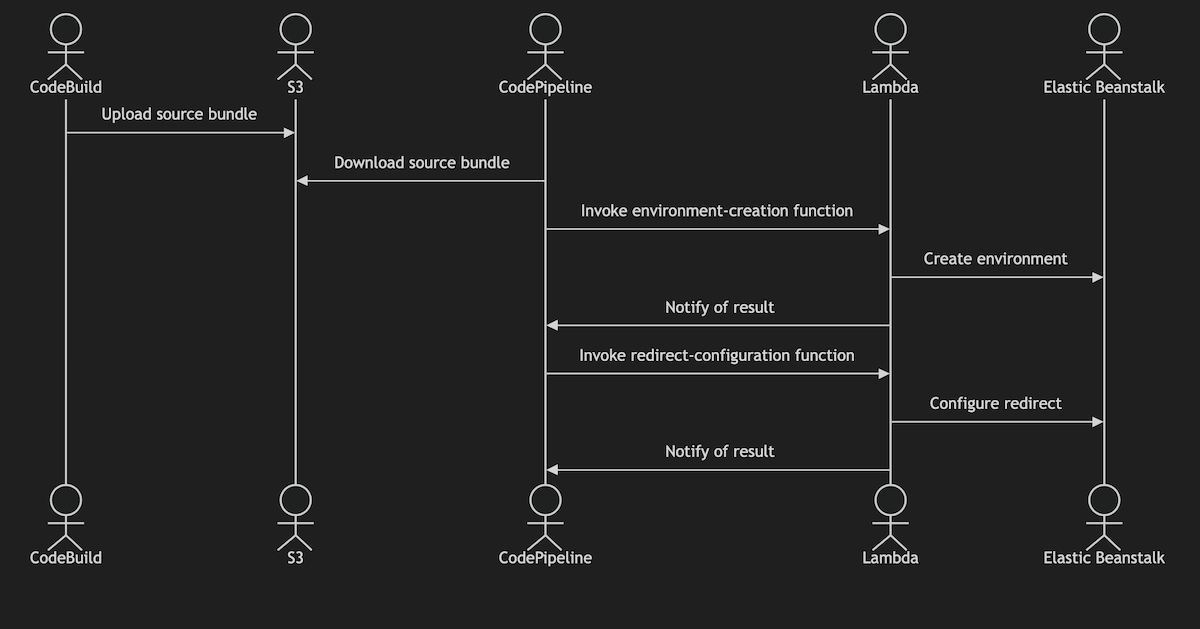

What we are mainly interested in here are the interactions of CodePipeline with Lambda, and Lambda with EB. Our main objective in improving this pipeline will be to refactor the CodePipeline action that deploys the source bundle to EB to use a Lambda function rather than the built-in EB deploy provider. Or, to express this as a modified diagram:

Given that the new Lambda function will be designed to create a new environment dynamically, this refactoring will enable us to rid the deployment pipeline of direct knowledge of the environment against which it is working.

I’ll go deeper into the code behind this refactoring in the second post in this series. Before we wrap up this first post, however, let’s examine in a general way what will be involved in creating a new environment dynamically.

Dynamic environment creation

In pseudocode creating a new environment dynamically will involve the following steps:

| Step | Description | Depends on steps |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Determine the live environment’s metadata | |

| 2 | Determine the staging environment’s metadata | 1 |

| 3 | Create an application version | |

| 4 | Create the staging environment | 2, 3 |

| 5 | Wait for the staging environment to be ready | 4 |

Most of these steps will depend for their internal workings on the AWS SDK EB client; the exception is step 2 (determining the staging environment’s metadata), whose return value will be solely dependent on step 1’s return value. The completion of these steps will result in the creation of the following:

- A staging environment to which the next version of our application is deployed

- Metadata about the live and staging environments that can be consumed by subsequent pipeline actions.

Conclusion

I started this post by analyzing a flaw in the design of the deployment pipeline for this blog’s WordPress application—namely, that the pipeline needs to have direct knowledge of the environment to which it is deploying the application. I then defined “blue-green deployment” and examined how the cyclical nature of this deployment strategy maps to functions provided by EB, specifically functions for creating, swapping and terminating environments. Finally I outlined the design for a dynamic environment-creation process that can be used to support a blue-green deployment strategy in the context of automated deployments to EB. In my next post I’ll go into the code behind each of the steps in the newly designed environment-creation process.